Why Insurance Won't Cover Therapy

Here is a hard truth: even therapists have trouble agreeing on what exactly they do. And this confusion is sabotaging mental health access. In this article, I’m going to analyze therapy’s different identities and suggest a way forward to getting more people the care they need.

Let’s get one thing out of the way: therapy works. A good therapist doesn’t just chat about the weather but triggers powerful changes that impact not only mood but long-term health and the ability to contribute meaningfully to society. Some approaches, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), already have a large and consistent body of evidence proving efficacy. Other types may be no less effective, are impossible to deny when experienced, but are challenging to study using existing academic tools. Anyone who thinks that therapy is pseudoscience has a glaring intellectual blindspot.

A good therapist triggers powerful changes that impact not only mood but long-term health and the ability to contribute meaningfully to society.

Many people suffering from mental health conditions face frustration when they need to find a therapist — waiting lists for in-network providers are long, and going out-of-network means patients themself must pay for the cost of treatment. The difference between going to an in-network versus an out-of-network therapist can be between a ~$20 copay for each session versus paying $200 per session and filling out paperwork for out-of-network benefits that reimburse $40 after accumulating $10,000 in costs.

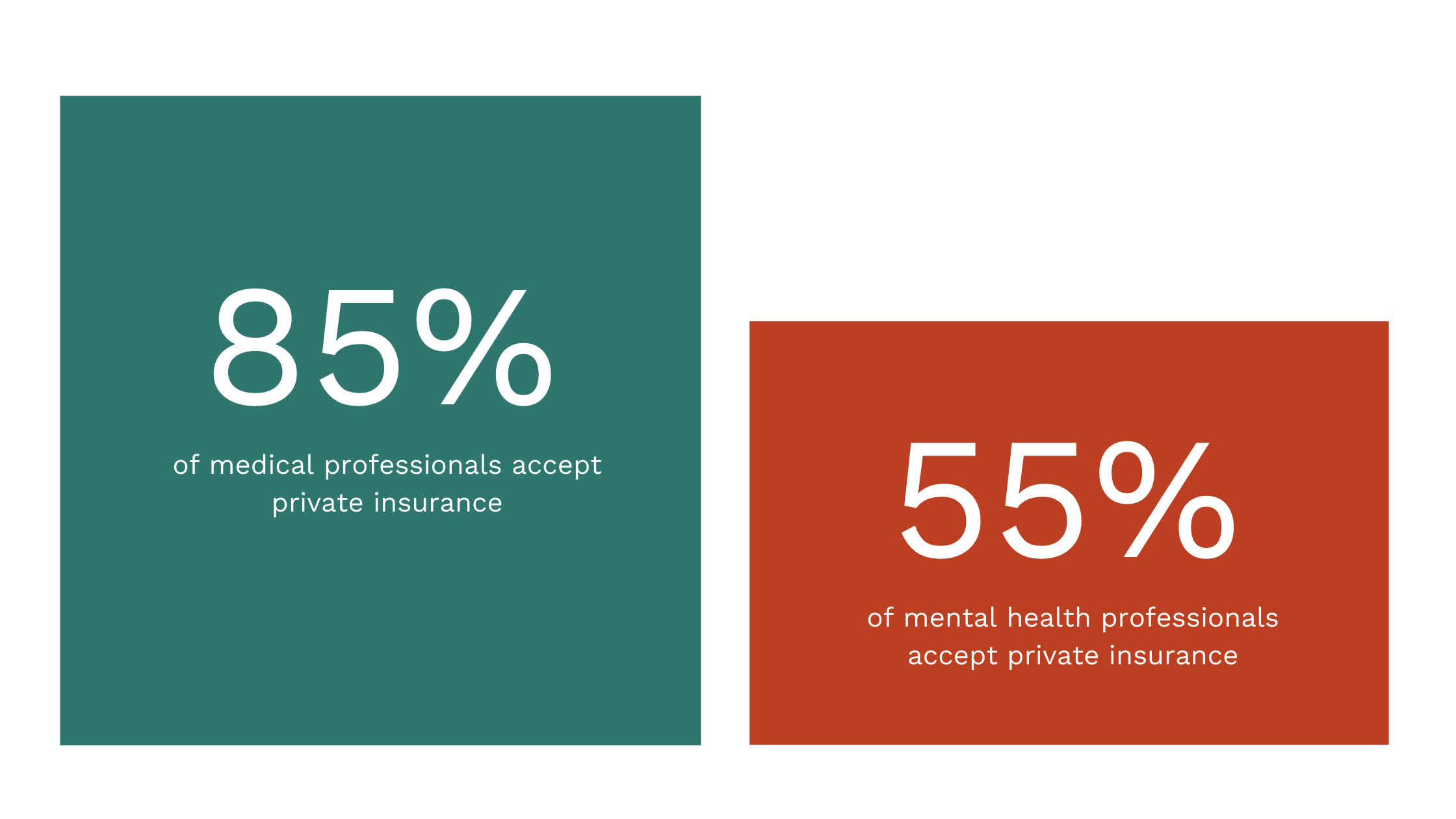

When it comes to mental health, most therapists are out-of-network providers who expect direct payment from patients. Americans are used to in-network economics when it comes to healthcare. Most other healthcare professionals provide their services within a network. For example, the bill for visiting your family physician for an annual checkup is a $20 copay. In 2010, 89% of all medical professionals accepted private insurance, contrast this with psychiatry where only 55% of professionals accepted.

Despite efforts like the Mental Health Parity Act (MHPA), the reality is that many people who need care are unable to get it. Beyond the personal suffering involved in living with untreated mental health conditions, this state of the world leads to downstream consequences of higher rates of chronic disease and emergency room visits that further tax the American healthcare system.

The reality is that many people who need care are unable to get it.

Why Therapists Don’t Take Insurance

When therapists talk about the lack of in-network mental health services, they usually point out two negative incentives that they face for accepting insurance.

- Insurance companies set a fixed price well below what therapists can charge in the private markets. A therapist who accepts private insurance gets paid $50-$80 per session, while the market rate in places like the Bay Area can be several times that. A disturbing consequence of this economic incentive is that the most talented therapists will choose easier, wealthier clients rather than the neediest.

- Working with insurance companies is onerous to therapists – the process of joining a panel is confusing and bureaucratic, and accepting insurance means the therapist must spend (uncompensated) time filling out paperwork and deal with time-consuming audits of their work.

A common next step is a critique of the unfeeling, profit-conscious insurance system. Yes, it can be tricky to align social and humanitarian objectives with economic ones. Human lives are precious, with value beyond the dollars they earn or cost. But something is missing about this perspective. It tends to cast insurance companies as cartoon villains who want to keep the nation ill. It doesn’t explain why, of all the harsh cost-cutting measures that insurance companies could employ, mental health seems to be the only treatment singled out. Is it because all the decision-makers have the out-dated belief that mental illness isn’t a real illness? Or do they have a personal vendetta against therapists? I think the real reasons are more complicated, with roots in identity confusion.

It tends to cast insurance companies as cartoon villains who want to keep the nation ill.

What the Heck is Therapy?

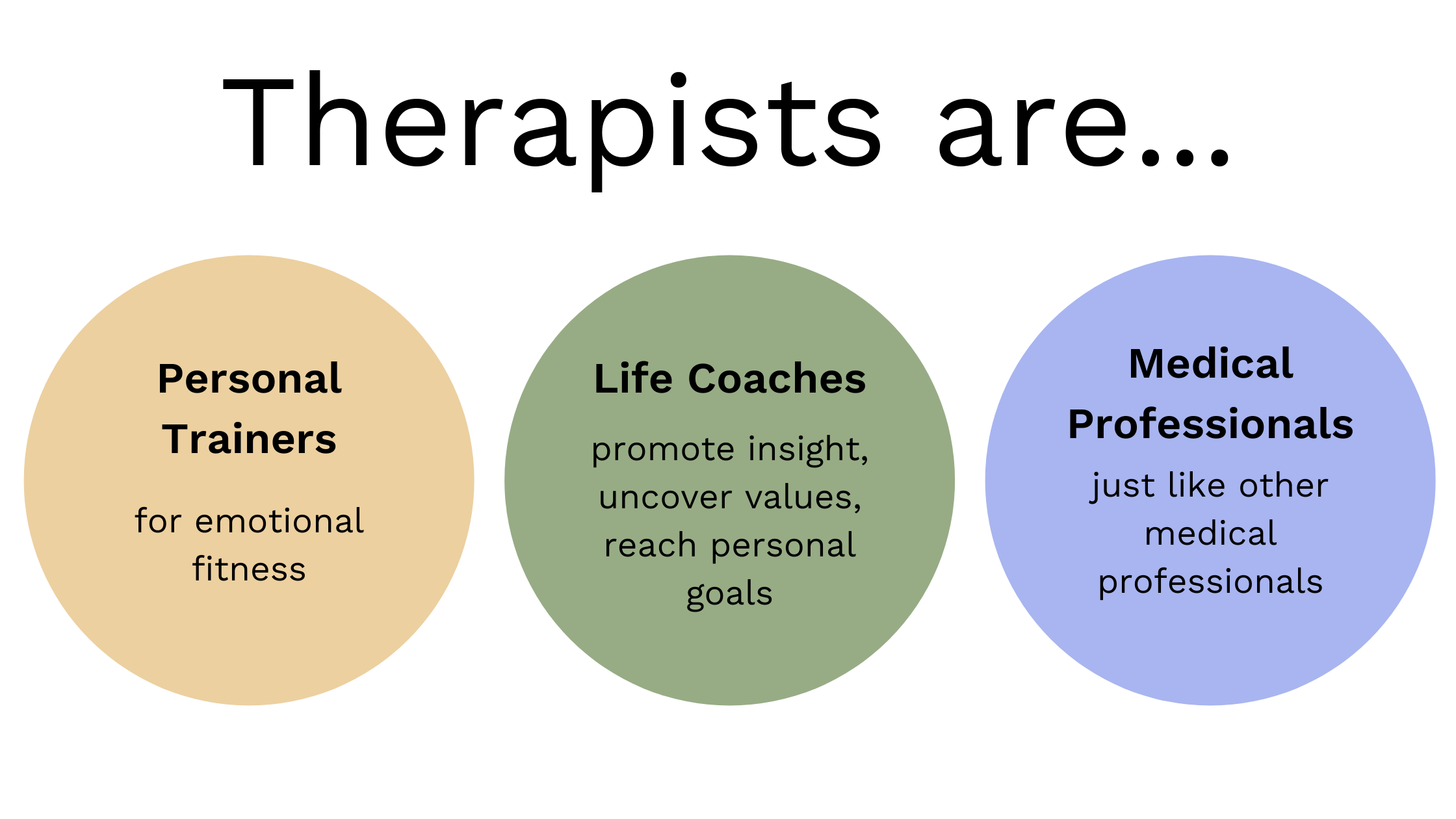

To understand why therapy is so difficult to access within healthcare, we have to disentangle its different identities and understand what we are buying. There are three ways of understanding the value-proposition of therapists:

- Therapists are personal trainers for emotional fitness. Therapy is a natural part of a wellness lifestyle, much like a gym membership.

- Therapists are life coaches who provide a personalized continuing liberal arts education that promotes insights and abilities. This service confers a life advantage similar to privileged parents and a premium education.

- Therapists are medical professionals who treat medical conditions just like providers.

Do you already see the problem from the insurance perspective? These are very different services, not all of which can easily be handled by the healthcare system.

1. Therapy as emotional fitness gym

The analogy of a therapist to a personal trainer at the gym makes a lot of sense: a therapist can enhance mental health for people who are doing more-or-less-okay like how going to the gym improves physical health for more-or-less-healthy people. Everyone can benefit from therapy.

But a monthly membership at 24 Hour Gym costs $40, a 1-hour session with a personal trainer at Equinox, a premium gym, costs $110. Is there a good reason that an emotional fitness trainer costs twice that? Should health insurance pay for a high-end wellness service? Subsidizing Equinox memberships would be cheaper.

An Equinox membership is cheaper.

2. Therapy as life coaching

Part of the complexity of mental health is that many different types of professionals are legally allowed to call themselves therapists, and the scope of therapy is changing.

- Psychiatrists hold a medical degree & license, but they specialize in the mind.

- Psychologists hold a doctorate — Ph.D., PsyD, or an EdD degree & licensed through the American Psychological Association (APA), having studied specialties such as PTSD or sleep disorders. Unlike psychiatrists, psychologists are not as trained in pharmacology and do not prescribe medication.

- Other licensed therapists hold a master’s degree, typically in clinical psychology. In California, there are three main types of licenses regulated by the Board of Behavioral Sciences (BBS): the licensed marriage and family therapist (LMFT), the licensed professional clinical counselor (LPCC), and the licensed clinical social worker (LCSW). Psychologists and master’s-level therapists have similar legal rights; the main difference is that only psychologists can perform assessments for patients they are not treating, such as part of a court testimonial.

- To add even more confusion, then there are the coaches who may hold various certifications in coaching, or none at all. Coaches specialize in diverse areas ranging from working with executives to reaching weight loss goals. The legal difference between a therapist and coach is confusing and still getting defined. Here’s what we know now: unlike therapists, coaches aren’t licensed to diagnose and treat severe diseases like substance abuse, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorders. And because no US laws regulate them, coaches do not have the right to protect client confidentiality if subpoenaed.

In their capacity as a social worker or life coach, therapists facilitate resilience & self-awareness, supplement education on life skills, and even share insights from philosophy. For someone coping with life difficulties, this is critical support that can make all the difference. Therapy can also benefit the already-privileged, boosting them from the top 10% to the top .1%. Even venture capitalists see therapy as high-ROI executive development.

Venture capitalists see therapy as high-ROI executive development.

The emotional fitness and therapist-as-life-coach businesses run on a familiar subscription model, which incidentally, is a better business. They are also elective: nice to have, but not medically necessary. Both incompatible with the mechanism of insurance systems:

We have health insurance because sometimes there are expensive disasters. So, instead of going bankrupt or just dying because we can’t afford medical bills, we decide that we’d rather pay a little bit while we are healthy, then we are protected if we get ill. In economics, this strategy is called consumption smoothing. When elective services get added to an insurance system, this introduces a moral hazard: people can game the system by using as much of the service as possible because someone else is paying the bill. When everyone starts using the service, there’s no one left to pass off the check. Insurance premiums have to increase, and patients are now spending the same money if they had paid directly out of pocket.

We have health insurance because sometimes there are expensive disasters.

3. Therapy as a medical service

Most people see therapists as medical professionals, and the shortage of therapists is most problematic in a medical setting. Mental health research shows that medication may not be the best or safest treatment. Even though psychotherapy works better than medication for many conditions, most patients get drugs instead because they cannot access therapy through medical channels. 1 in 6 adults took a psychiatric drug in 2013. For specific issues like insomnia, experts have taken the even stronger stance that therapy, not drugs, is the better first-line intervention. We need the help of therapists in a medical setting, so why are they missing?

For various reasons, many therapists have separated philosophically from the rest of the medical community. The goal of medicine is to make medically necessary improvements as safely and as quickly as possible. Treatment starts with analyzing the issue (while considering contexts like personality, physiology, comorbidities), setting a realistic target of what success means, and carrying out a treatment plan. The ultimate goal of treatment is to stop needing treatment. Counterintuitively, many mental health experts warn against labels, diagnoses, and exact treatment plans, preferring open-ended and adaptive relationships. Diagnostic criteria for conditions shift. Debates rage about the validity of each edition of the DSM (homosexuality was still a diagnosable disorder in DSM III published in 1980). The movement to shift terminology away from referring to people as patients but rather clients emphasizes an equal relationship and the mindset that there is nothing inherently wrong with the client.

Alot of therapists are uncomfortable even with the concept of medical necessity. They point out that it invites moral questions like whose pain is real pain, stigmatizes mental illness, and discourages people from seeking help. But analysis, triage, and tough decision-making are realities of practicing medicine. We do not treat a patient with well-managed diabetes in the emergency room. In a hospital, a stabbing victim needs more attention. All of this means that therapy economics is really weird.

Therapy economics is really weird.

Therapy is usually priced only by time-in-session, not by the specific operations delivered within the session, the condition treated, or even expected outcomes. This extreme fee-for-service model in a medical setting would be like paying a surgeon to perform surgery at an hourly rate equal to a family care doctor going through a routine checkup. Given that therapists are humans who respond to economic incentives, this means everyone would do a lot of checkups, and no one is left to do surgery.

Given that therapists are humans who respond to economic incentives, this means everyone would do a lot of checkups, and no one is left to do surgery.

Medical ethics say that unless the patient has consented to be part of a study, the treatment should have existing evidence of its efficacy. This standard would exclude emerging therapeutic approaches used by many therapists but lack academic data, such as EMDR. It’s a blessing in a way; the mental health community is amazingly creative and committed to the continuing education of its providers. The flip side is that impatience with the process of collecting evidence means that many commonly delivered therapies lack an evidence base, so medicine (and insurance) sees mental health as an unregulated wild-west. Part of the reason for this is cultural, but there are also natural challenges for regulating a private conversation. The CPT code for therapy is 50-minute psychotherapy, not delivered CBT 5mg, EFT 10mg.

While medical systems value teams that work together to provide patient-centered care, therapists are mostly individual practitioners in private practice. When most therapists disconnect from the medical system, patients find therapists through trial-and-error on google or standalone online services, rather than a referral through their primary care physician. Patients must face the daunting prospect of identifying the appropriate specialty alone.

So What Now?

Every person deserves mental health care. But for us to get there, more therapists need to be willing to work in a medical setting. This does’t mean therapists should work for free; they need to earn a living wage and be fairly compensated for doing valuable work! Insurance reimbursement should be higher than it is now. The reimbursement red tape needs to get fixed. However, I do think therapists need to cooperate with other medical professionals and design products that can fit within healthcare. Ultimately, redesigning therapy is a win-win for everyone: patients, insurance, and therapists.

Tags: Healthcare